Do you know that coastal phytoplankton is able to adapt to iron limitation?

Oceanographers have long understood that phytoplankton in the open ocean tend to have lower iron (Fe) requirements and/or more strategies for obtaining Fe from the environment. Adding a new twist to the established paradigm, Mackey and co-workers (2015, see reference below) show that coastal Synechococcus from the New England shelf is capable of dynamic, multitiered Fe adaptation. Their original approach was to compare growth, photophysiology, and quantitative proteomics of two Synechococcus strains from different Fe regimes.

The revealed competence of the coastal phytoplankton specie allows it to thrive over a broad range of Fe concentrations by partitioning Fe among different uptake and storage proteins as seawater Fe levels change. Conversely, a Synechococcus strain from the open Atlantic Ocean does not have this multitiered protein-based response. The ability of the coastal strain to acclimate to a wide range of Fe conditions comes with a cost: cells must invest nitrogen to make the proteins. Persistently low nitrogen levels in the open ocean may prove too costly for the oceanic Synechococcus strain, which has eliminated many Fe response genes from its genome. In contrast, higher nutrient availability closer to land affords coastal Synechococcus the flexibility to retain these proteins and so thrive even when and where Fe levels are low.

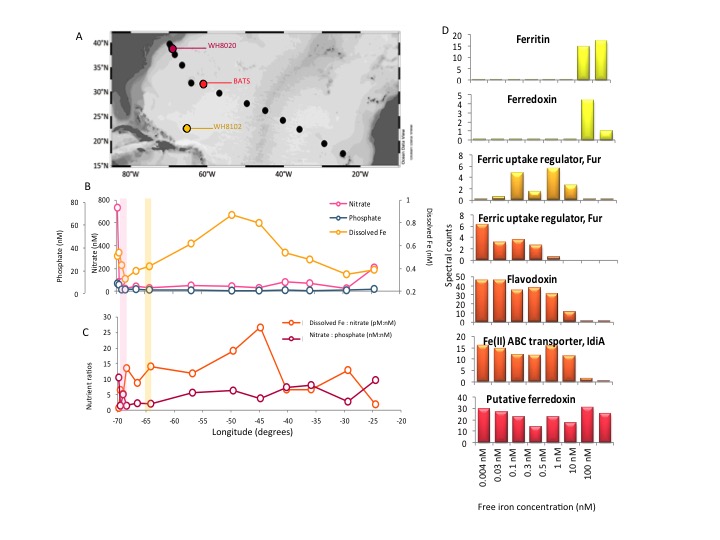

Figure: A) Locations of two strains of Synechococcus, the coastal WH8020 and Southern Sargasso WH8102, relative to the U.S. North Atlantic zonal section GEOTRACES (GA03) iron, nitrate and phosphorus concentrations. B-C) Fe concentrations were high in the central north Atlantic Ocean due to dust deposition, while coastal waters can have lower amounts of Fe relative to nitrogen. D) This variability is reflected in the highly dynamic protein response of the coastal phytoplankter Synechococcus WH8020, with Fe uptake, storage, and regulators varying with Fe abundance, allowing it to survive over a greater range of Fe concentrations. The oceanic strain has lost the ability to make many of these proteins, which may help it conserve nitrogen (as protein) in the open ocean where nitrogen is scarce. Click here to view the figure larger.

Reference:

Mackey, K. R. M., Post, A. F., McIlvin, M. R., Cutter, G. A., John, S. G., & Saito, M. A. (2015). Divergent responses of Atlantic coastal and oceanic Synechococcus to iron limitation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(32), 9944–9949. doi:10.1073/pnas.1509448112