26 May 2011, by Taryn Noble and Andrew Bowie

We are currently steaming across the South Fiji Basin situated at 30o 30‘S having finished sampling all the stations along the 30oS line of latitude. The topography of the surrounding seafloor is very interesting, with all sorts of seamounts and ridges, since we are approaching the boundary between the Indo-Australian and the Pacific plates. Seamounts are extinct volcanoes that have never reached the surface, and form underwater mountains in the ocean. The interaction of deep sea currents and the seamounts brings nutrients to the upper water column and provides ideal habitats for sea life. We have steamed past the Tui and Kiwi Seamounts and the Devonport Seamount Chain, as we head towards the Kermadec Ridge and Trench, and our new sampling stations along the 32oS line of latitude.

Our weather has been dominated by northerly winds, bringing relatively humid air (~85% humidity) southwards. We were anticipating rough weather for our mega-station yesterday due to a low pressure system moving northwards; however we faired well, with only 25 knots of wind and a fairly confused, choppy sea, rather than particularly large swells. The mega-station went very well with all activities including the McLane pumps operating successfully. Today we have a content, if rather exhausted, bunch of scientists as both shift-teams worked hard to process and collect all the seawater.

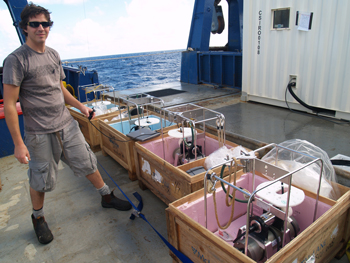

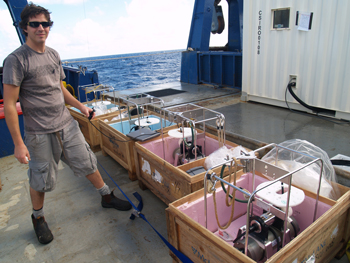

In this blog, the McLane pump deployments are discussed, the third operation onboard this GEOTRACES GP13 cruise. The McLane pumps are in situ pumps that draw in ambient water though a series of filters, collecting any particles suspended in the seawater. The pumps are made up of a plastic filtering system and a rotary pump protected by a stainless steel frame. The materials used in the McLane pumps include high quality plastics and metals (aluminium and titanium) that prevent contamination of the filter sample.

Sample filters are placed onto the 142 mm filter holder, which is designed to spread the seawater evenly across the entire filter surface and minimise turbulence. A rotary pulse pump located downstream of the filter, pumps the seawater though the filter system (up to volumes of 25,000 L). The volume of seawater drawn through the filter is recorded by a flow meter, which measures the pump exhaust flow. The pumps are programmed on the deck before deployment using a timer system. After a period of time that allows the pump to reach the desired depth, the pumps are set to start pumping for a set duration. There are four pumps onboard, which are used to sample water column depths of 30, 100, 300 and 1000 m.

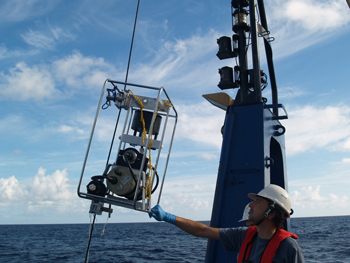

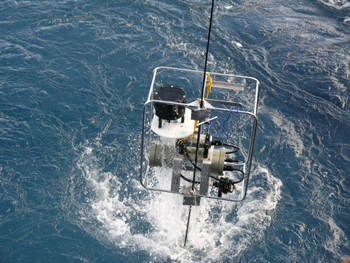

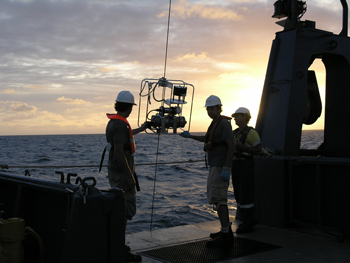

To deploy the pumps, a heavy weight is first attached to the sheathed steel wire, using the trace metal friendly block described in blog 3. Once the weight is at least 100 m below the surface, the wire is brought closer the ship using the A-frame, so that the first pump can be clamped onto the wire. This is quite a difficult job that takes at least three people since the pump, which weighs about 50 kg, has to be lifted close to the wire to attach it. A pressure sensor is attached to wire where the first pump is located to determine the maximum depth. The wire is then taken out to the desired depth, where the next pump is attached and so on, until all four pumps have been attached to the wire so that they sit at 30, 100, 300 and 1000 m depths. After a period of 1 hour of pumping, the pumps are brought back to the surface, and the filters holders taken directly into the clean container, where they are further divided for future analysis and stored in the freezer.

The McLane pumps are deployed twice, using two different types of filters, for a variety of different analyses. The first deployment uses a quartz microfiber filter. This filter collects suspended particles for the analysis of trace elements, as well as major elements like particulate organic carbon and nitrogen. For the second deployment, polycarbonate filters are placed in the filter holder. These filters are used to collect suspended particles for analysis of stable isotopes as well as radiogenic isotopes, protactinium and thorium. Information about the composition of particles suspended in the seawater is extremely valuable in combination with the composition of respective elements dissolved in seawater. For example, this type of information allows scientists to make estimates about the amount of carbon exported to the deep ocean from the surface. This is particularly important part of the carbon cycle to understand since the ocean has absorbed 30 to 40 % of all the carbon dioxide released by humans since the industrial revolution. The oceans carbon reservoir is 50 times larger than that of the atmosphere; therefore quantifying the fluxes of carbon between the atmosphere and ocean is essential for our broader understanding of human-induced climate change.